Transamazônica: after half a century, residents reveal the backstage of an unfinished work

The legacy of over 4,000 kilometers of the highway crossing seven Brazilian states is the cornerstone of discussions

It was October 9, 1970. After leaving Brasília's political routine and diving into a long trip of nearly two thousand kilometers towards the corners of the Amazon region, as far as the Xingu zone in the western part of Pará, President of Brazil, General Emílio Garrastazu Médici, takes part in a public ceremony in the city of Altamira. On a particularly hot day, he fells down a tree over 50 meters high as a symbolic act that sets the beginning of the main infrastructural megaproject of the military government in the North of Brazil – the Transamazônica Highway.

Listen to the comment on this news:

In his speech, Médici said that the undertaking would make Amazon known by the entire country. In the General's view, the region was marked by “backwardness and poverty”. The highway, therefore, would offer the development the Amazon region needed so badly. “I bring to the Amazon the government's and the people's reliability that Transamazônica shall be, after all, the path to achieve the region’s true economic vocation and to make itself closer and more accessible to the work of Brazilians from all sites of the country,” announced Medici.

Even though Médice, himself, had been the greatest encourager of the project, he could not have foreseen the extent of the social impacts stemming from the Project and how hard they would hit Brazilian people’s lives as a whole, especially in the North and Northeast regions. Stretching over 4,223 kilometers, Transamazônica is still one of the largest highways in the world, crossing seven Brazilian states and connecting two regions of the country in a variety of ways. Fifty years later, life is still pulsating along the BR-230 – people who succeeded as promised in the 1970s and people who still pursue their dreams.

Two years after his first visit, Medici would return to the locality on September 27th. At this time, the president inaugurated the first 1,253-kilometer stretch of the highway, linking the municipality of Estreito in the state of Maranhão to Itaituba in the state of Pará. Two months later, in November, Netinha’s family, who was six years old by then, arrived from Ceará along with other people from the Northeastern states. These people were brought by the government to occupy the area which was meant to be “a land of no people for a people of no land”.

“We left Ipaumirim, right in the heart of the hinterlands. We were nine: my father, mother and seven children. Five women and two men. We all managed to get here safe and sound: no one got sick, except for occasional bellyaches here and there”, recollects Maria Ivonete Coutinho da Silva, who is now a professor at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), in Altamira. She studies the highway that changed her life for good.

Her parents, Francisco and Francisca, arrived with Maria Ivonete and the other children at the camping site in Altamira after a laborious route that involved bus trips, two flights in Brazilian Air Force (FAB) planes and a journey in the back of a truck. While his wife and children shared a shack with two or three other families, Chico Barbeiro, a man with no experience in agriculture, went out with other settlers in search of a piece of the life promised to him.

“We wanted a piece of land to work, to live on and to grow rice, beans, and then, pepper, cocoa, whatever else. But the government's project, by offering land to poor families did not mean to give them the property of the land. So much that many people today still do not have the title deeds. The underlying intention was to open up an economical front in the Amazon for the inflow of both national and international capital”, analyses Maria Ivonete Coutinho. “But people struggled and manage to subvert this order. In the scope of this project, which was not meant for the benefit of the working class, we managed to get along some way, but with a great deal of resistance”, ponders the Professor. Today, Ivonete Coutinho, registers the 50th anniversary of Transamazônica with her academic research, and keeps on working towards a more promising future for the region.

In her doctorate thesis “Mulheres migrantes na Transamazônica: construção da ocupação e do fazer política” [Migrant women in Transamazônica: the establishment of the occupation and of policy making], Professor ‘Netinha’ researched on how the female presence was determinant for the occupation of the Xingu region. The research shows how wives were the ones who made husbands see the area not only as a working place, but as a home where they could build meaningful bonds and roots.

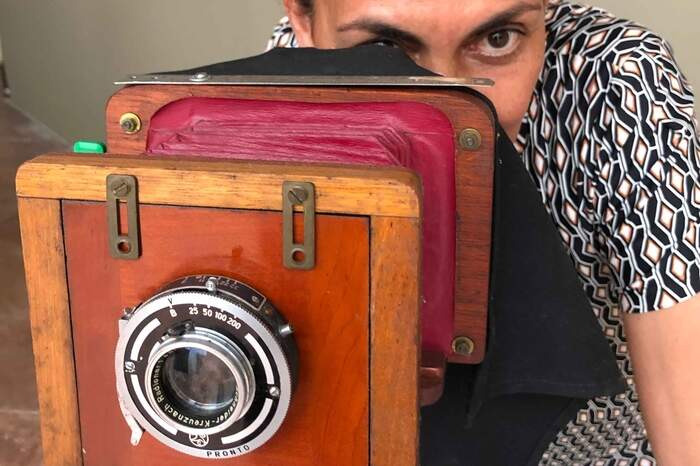

"When I started in photojournalism, my dream was to be a war photographer. I once said that, back in 1987, to a senior photojournalist workmate, and he replied: you are already on the battle field, your war is right here, in the Amazon" - Paula Sampaio, is a photographer.

For Professor Maria Ivonete Coutinho, it is precisely this understanding of the common sense that is needed nowadays. “Today, I go back to Transamazônica and what I see is essentially livestock activities, but lack of investment in family farming. We get to those travessões [communities along the highway] and people don't have a single chicken to sell, or tomatoes, pumpkins, rice...instead, whatever they need they have to pay for. I believe there is no incentive policy in that direction. Such a productive land. The picture that emerges is large livestock and cocoa producers on one side and the small ones living in unfavorable conditions”, she regrets.

The Highway still faces production challenges

At a certain pace, the federal government announces the conclusion of one more stretch of Transamazônica. Since the beginning of the construction works, twelve presidents have governed the country and delivered sections of it. But none of them managed to overcome the colossal challenge posed 50 years ago, which was to pave and structure the entire length of the highway. The most recent stretch was inaugurated in June this year, when President Jair Bolsonaro took part in an event in southeastern Pará in celebration for the 102 km of paved road, connecting the municipalities of Novo Repartimento and Itupiranga.

Of over 4,200 km of the Transamazônica extension, nearly 1,700 correspond to dirt track, unpaved road which makes traffic extremely difficult (due to the intense dust) for truck drivers who, like the settlers of 50 years ago, come from the most diverse corners of Brazil to earn a living transporting goods. If one drives from Altamira heading to Medicilândia – a city named after the military president who started the road – it is possible to notice that the paving is relatively recent and well done. The 80-Km route is covered in about an hour by car. However, right after this stretch of road, the asphalt gives way to red earth and the problems caused by the lack of infrastructure.

"You ask me if here is bad... ‘bad’ is too mild a word to describe this place. It is awful! This year, they abandoned the road”, comments Cláudio Almeida, a truck driver who transported chicken at a certain point on the highway, five kilometers away from the center of Medicilândia, where the asphalt ends. A little further, another driver, Dionilson Barros travels with a load of cocoa coming from Uruará. He says that over the 30 years driving back and forth the 100 kilometers between the two cities, it's like time has stood still… little has changed. “The road is ruined and nobody takes action. The situation is very bleak. Some things have improved, I agree, but lately this section has been abandoned. This piece of road from here to Rurópolis has got to be finished”, ponders Dionilson.

Even the less experienced drivers will easily admit that to face Transamazônica highway, one needs courage and patience. “I came from Uruará these days, and it was a four-hour bus ride. The road is pretty rotten. A lot of dust, holes, and when it rains, it's too much mud and quagmire”, stresses Tarcísio Teixeira, 19 years old.

In the same occasion in which the federal government delivered the most recent asphalted stretch of the BR-230, the minister of Infrastructure, Tarcísio Gomes, and the director of Departamento Nacional de Infraestrutura de Transportes [National Department of Transport Infrastructure] - DNIT, Santos Filho, executed a service order valued at R$202 million destined to the construction of a new bridge over the Xingu River.

The work is expected to start in 2022, after elaboration and approval of the project, which is supposed to last two years. This new project is another step towards the highway structuring process.

For many of those who live alongside the road, the promise generates expectation, but the reality is still harsh as the river crossings depend on ferries on the way from Anapu to Altamira.

Conflicts and survival challenges

“When I started in photojournalism, my dream was to be a war photographer. I once said that, back in 1987, to a senior photojournalist workmate, and he replied: you are already on the battle field, your war is right here, in the Amazon”. Carrying her shoulder strap lens, Paula Sampaio just went for it. When she got to the front in 1990, in Altamira. She realized herself staring at Transamazônica road. She describes it as “a shiny red land snake”. Thus, she started registering the daily life throughout the road.

Paula Sampaio was born in Belo Horizonte. She got based in Pará state and found on Transamazônica the paths she would follow during the next decades, starting a job which has lasted for more than 30 years. Everything she records when taking pictures and interviewing the locals is available for free use by students, researchers, non-governmental organizations, unions and institutions which work on the defense of that people and of the environment – trying to use her work to help men and women who live there anyhow.

“The life stories collection and the relationship of those people with the environment crossed by the road is remarkable. The set of relationships and the way those communities are organized, creating spaces for resistance, and the strength of nature which embraces everyone around here, even so damaged, pulsates in me forever", says the photographer.

See some images by Paula Sampaio about the Transamazônica:

Indigenous people, riverine populations, and small-scale farmers are some of the characters who try to live in the area under the road influence. They claim for their space among the big companies and owners of huge land areas. The road experiences turmoil along all its length, caused by agrarian conflicts and the everlasting dispute between indigenous and large rural producers.

Conflicts and new projects still remain in the region

In February 2005, the North American missionary Dorothy Stang’s murder showed to the world a sample of how dangerous life is for those who fight for the rural workers’ rights on Transamazônica road. Crimes such as, sexual exploitation, traffic and illegal mining are frequently in the police news. Still, life persists and people persevere, due to their inherent resilience and refusal to give up.

“Life here is pretty good. It is calm, better than in Altamira, where it is hectic. There is no crime”, justifies Regiane Rodrigues Ribeiro, a 21-year young nursing student who resides in Leonardo Da Vinci community, Vitória do Xingu. On the weekends in that small town placed on Transamazônica, she goes to the borders of the road to make a living. She sells pamonha, a traditional Brazilian snack made with corn grown in her grandfather’s ranch by her father and husband, who is from Minas Gerais state and came to Pará to pursue a better life in the region when the road had just been opened.

Regiane grew up listening to stories about how hard life was for her family to succeed after coming from so far place to an unknown land. Recently, the student has observed a similar process: she has witnessed the changes imposed by the Belo Monte hydroelectric power plant to her community. “About Belo Monte, I don’t think there was a lot of improvements for us here. Life changed a lot during the construction. A lot of people came to live here, the crime rate went up high, but when it was over, it was the same as before, when we used to know everyone and talk to everybody. During that period, many outsiders came. It was a mess. The flats for rent were packed. The movement never ceased. When they finished, only the empty houses were left behind”, remembers the student, who also says she liked the life at the borders of BR-230 road.

"Life here is pretty good. It is calm, better than in Altamira, where it is hectic. There is no crime" - Regiane Rodrigues Ribeiro is a student.

“There was no pavement in this area before, now there is. Right here in the town, things are much better. I know a lot of people who have jobs here, next to the road. People come from outside and we get to know many cultures. During the week, I work at the health center”, she says. She is a nurse assistant and is currently attending college in this area. The classes are in hybrid format, both online attended from home and in-person classes, in Altamira, where she goes every week. There, Regiane has in-person instruction in a private institution, which recently is based in the region. “For me, this peaceful place is wonderful. It looks like the country, but there is internet connection, electricity, all cool”, the young lady smiles, sitting by the side of the road, waiting for the next big thing Transamazônica will bring to her life.

Transamazônica: a colossal challenge

- With its 4,223 kilometers of extension, Transamazônica road starts is Cabedelo city, in Paraíba state, and finishes in Lábrea, in Amazonas;

- It crosses seven states: Paraíba, Ceará, Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí, Pará e Amazonas;

- The road crosses 63 municipalities;

- Its extension crosses three Brazilian ecosystems: Amazônia Rainforest, Caatinga and Cerrado.

Palavras-chave

COMPARTILHE ESSA NOTÍCIA